Fifty Years

in the Church

of Rome

by Charles Chiniquy

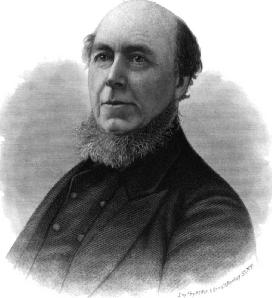

Charles Chiniquy

1809-1899

CHAPTER 35

The people of Beauport had scarcely been a year enrolled under the banners of temperance, when the seven thriving taverns of that parish were deserted and their owners forced to try some more honourable trade for a living. This fact, published by the whole press of Quebec, more than anything forced the opponents, especially among the clergy, to silence, without absolutely reconciling them to my views. However, it was becoming every day more and more evident to all that the good done in Beauport was incalculable, both in a material and moral point of view. Several of the best thinking people of the surrounding parishes began to say to one another: "Why should we not try to bring into our midst this temperance reformation which is doing so much good in Beauport?" The wives of drunkards would say: "Why does not our curate do here what the curate of Beauport has done there?"

On a certain day, one of those unfortunate women who had received, with a good education, a rich inheritance, which her husband had spent in dissipation, came to tell me that she had gone to her curate to ask him to establish a temperance society in his parish, as we had done in Beauport; but he had told her "to mind her own business." She had then respectfully requested him to invite me to come and help to do so for his parishioners what I had done for mine, but she had been sternly rebuked at the mention of my name. The poor woman was weeping when she said: "Is it possible that our priests are so indifferent to our sufferings, and that they will let the demon of drunkenness torture us as long as we live, when God gives us such an easy and honourable way to destroy his power for ever?"

My heart was touched by the tears of that lady, and I said to her: "I know a way to put an end to the opposition of your curate, and force him to bring among you the reformation you so much desire; but it is a very delicate matter for me to mention to you. I must rely upon your most sacred promise of secrecy, before opening my mind to you on that subject."

"I take my God to witness," she answered, "that I will never reveal your secret." "Well, madam, if I can rely upon your discretion and secrecy, I will tell you an infallible way to force your priest to do what has been done here."

"Oh! for God's sake," she said, "tell me what to do."

I replied: "The first time you go to confession, say to your priest that you have a new sin to confess which is very difficult to reveal to him. He will press you more to confess it. You will then say:

"'Father, I confess I have lost confidence in you.' Being asked 'Why?' You will tell him: 'Father, you know the bad treatment I have received from my drunken husband, as well as hundreds of other wives in your parish, from theirs; you know the tears we have shed on the ruin of our children, who are destroyed by the bad examples of their drunken fathers; you know the daily crimes and unspeakable abominations caused by the use of intoxicating drinks; you could dry our tears and make us happy wives and mothers, you could benefit our husbands and save our children by establishing the society of temperance here as it is in Beauport, and you refuse to do it. How, then, can I believe you are a good priest, and that there is any charity and compassion in you for us?'

"Listen with a respectful silence to what he will tell you; accept his penance, and when he asks you if you regret that sin, answer him that you cannot regret it till he has taken the providential means which God offers him to persuade the drunkards.

"Get as many other women whom you know are suffering as you do, as you can, to go and confess to him the same thing; and you will see that his obstinacy will melt as the snow before the rays of the sun in May."

She was a very intelligent lady. She saw at once that she had in hand an irresistible power to face her priest out of his shameful and criminal indifference to the welfare of his people. A fortnight later she came to tell me that she had done what I had advised her and that more than fifty other respectable women had confessed to their curate that they had lost confidence in him, on account of his lack of zeal and charity for his people.

My conjectures were correct. The poor priest was beside himself, when forced every day to hear from the very lips of his most respectable female parishioners, that they were losing confidence in him. He feared lest he should lose his fine parish near Quebec, and be sent to some of the backwoods of Canada. Three weeks later he was knocking at my door, where he had not been since the establishment of the temperance society. He was very pale, and looked anxious. I could see in his countenance that I owed this visit to his fair penitents. However, I was happy to see him. He was considered a good priest, and had been one of my best friends before the formation of the temperance society. I invited him to dine with me, and made him feel at home as much as possible, for I knew by his embarrassed manner that he had a very difficult proposition to make. I was not mistaken. He at last said:

"Mr. Chiniquy, we had, at first, great prejudices against your temperance society; but we see its blessed fruits in the great transformation of Beauport. Would you be kind enough to preach a retreat of temperance, during three days, to my people, as you have done here?"

I answered: "Yes, sir; with the greatest pleasure. But it is on condition that you will yourself be an example of the sacrifice, and the first to take the solemn pledge of temperance, in the presence of your people."

"Certainly," he answered; "for the pastor must be an example to his people."

Three weeks later his parish had nobly followed the example of Beauport, and the good curate had no words to express his joy. Without losing a day, he went to the two other curates of what is called "La Cote de Beaupre," persuaded them to do what he had done, and six weeks after all the saloons from Beauport to St. Joachim were closed; and it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to persuade anyone in that whole region to drink a glass of any intoxicating drink.

Little by little, the country priests were thus giving up their prejudices, and were bravely rallying around our glorious banners of temperance. But my bishop, though less severe, was still very cold toward me. At last the good providence of God forced him, through a great humiliation, to count our society among the greatest spiritual and temporal blessings of the age.

At the end of August, 1840, the public press informed us that the Count de Forbin Janson, Bishop of Nancy, in France, was just leaving New York for Montreal. That bishop, who was the cousin and minister to Charles the Tenth, had been sent into exile by the French people, after the king had lost his crown in the Revolution of 1830. Father Mathew had told me, in one of his letters, that this bishop had visited him, and blessed his work in Ireland, and had also persuaded the Pope to send him his apostolical benediction.

I saw at once the importance of gaining the approbation of this celebrated man, before he had been prejudiced by the bishop against our temperance societies. I asked and obtained leave of absence for a few days, and went to Montreal, which I reached just an hour after the French bishop. I went immediately to pay my homage to him, told him about our temperance work, asking him, in the name of God, to throw bravely the weight of his great name and position in the scale in favour of our temperance societies. He promised he would, adding: "I am perfectly persuaded that drunkenness is not only the great and common sin of the people, but still more of the priests in America, as well as in Ireland. The social habit of drinking the detestable and poisonous wines, brandies, and beers used on this continent, and in the northern parts of Europe, where the vine cannot grow, is so general and strong, that it is almost impossible to save the people from becoming drunkards, except through an association in which the elite of society will work together to change the old and pernicious habits of common life. I have seen Father Mathew, who is doing an incalculable good in Ireland; and, be sure of it, I shall do all in my power to strengthen your hands in that great and good work. But do not say to anybody that you have seen me."

Some days later, the Bishop of Nancy was in Quebec, the guest of the Seminary, and a grand dinner was given in his honour, to which more than one hundred priests were invited, with the Archbishop of Quebec, his coadjutor, N. G. Turgeon, and the Bishop of Montreal, M.Q.R. Bourget.

As one of the youngest curates, I had taken the last seat, which was just opposite the four bishops, from whom I was separated only by the breadth of the table. When the rich and rare viands had been well disposed of, and the more delicate fruits had replaced them, bottles of the choicest wines were brought on the table in incredible numbers. Then the superior of the college, the Rev. Mr. Demars, knocked on the table to command silence, and rising on his feet, he said, at the top of his voice, "Please, my lord bishops, and all of you, reverend gentlemen, let us drink to the health of my Lord Count de Forbin Janson, Primate of Lorraine and Bishop of Nancy.

The bottles passing around were briskly emptied into the large glasses put before everyone of the guests. But when the wine was handed to me I passed it to my neighbour without taking a drop, and filled my glass with water. My hope was that nobody had paid any attention to what I had done; but I was mistaken. The eyes of my bishop, my Lord Signaie, were upon me. With a stern voice, he said: "Mr. Chiniquy, what are you doing there? Put wine in your glass, to drink with us the health of Mgr. de Nancy."

These unexpected words fell upon me as a thunderbolt, and really paralyzed me with terror. I felt the approach of the most terrible tempest I had ever experienced. My blood ran cold in my veins; I could not utter a word. For what could I say there, without compromising myself for ever. To openly resist my bishop, in the presence of such an august assembly, seemed impossible; but to obey him was also impossible; for I had promised God and my country never to drink any wine. I thought, at first, that I could disarm my superior by my modesty and my humble silence. However, I felt that all eyes were upon me. A real chill of terror and unspeakable anxiety was running through my whole frame. My heart began to beat so violently that I could not breathe. I wished then I had followed my first impression, which was not to come to that dinner. I think I would have suffocated had not a few tears rolled down from my eyes, and help the circulation of my blood. The Rev. Mr. Lafrance, who was by me, nudged me, and said, "Do you not hear the order of my Lord Signaie? Why do you not answer by doing what you are requested to do?" I still remained mute, just as if nobody had spoken to me. My eyes were cast down; I wished then I were dead. The silence of death reigning around the tables told me that everyone was waiting for my answer; but my lips were sealed. After a minute of that silence, which seemed as long as a whole year, the bishop, with a loud and angry voice, which filled the large room, repeated: "Why do you not put wine in your glass, and drink to the health of my Lord Forbin Janson, as the rest of us are doing?"

I felt I could not be silent any longer. "My lord," I said, with a subdued and trembling voice, "I have put in my glass what I want to drink. I have promised God and my country that I would never drink any more wine."

The bishop, forgetting the respect he owed to himself and to those around him, answered me in the most insulting manner: "You are nothing but a fanatic, and you want to reform us."

These words struck me as the shock of a galvanic battery, and transformed me into a new man. It seemed as if they had added ten feet to my stature and a thousand pounds to my weight. I forgot that I was the subject of that bishop, and remembered that I was a man, in the presence of another man. I raised my head and opened my eyes, and as quick as lightning I rose to my feet, and addressing the Grand Vicar Demars, superior of the seminary, I said, with calmness, "Sir, was it that I might be insulted at your table that you have invited me here? Is it not your duty to defend my honour when I am here, your guest? But, as you seem to forget what you owe to your guests, I will make my own defense against my unjust aggressor." Then, turning towards the Bishop de Nancy, I said: "My Lord de Nancy, I appeal to your lordship from the unjust sentence of my own bishop. In the name of God, and of His Son, Jesus Christ, I request you tell us here if a priest cannot, for His Saviour's sake, and for the good of his fellow-men, as well as for his own selfdenial, give up for ever the use of wine and other intoxicating drinks, without being abused, slandered, and insulted, as I am here, in your presence?"

It was evident that my words had made a deep impression on the whole company. A solemn silence followed for a few seconds, which was interrupted by my bishop, who said to the Bishop de Nancy, "Yes, yes, my lord; give us your sentence."

No words can give an idea of the excitement of everyone in that multitude of priests, who, accustomed from their infancy abjectly to submit to their bishop, were, for the first time, in the presence of such a hand-to-hand conflict between a powerless, humble, unprotected, young curate, and his all-powerful, proud, and haughty archbishop.

The Bishop of Nancy at first refused to grant my request. He felt the difficulty of his position; but after Bishop Signaie had united his voice to mine, to press him to give his verdict, he rose and said:

"My Lord Archbishop of Quebec, and you, Mr. Chiniquy, please withdraw your request. Do not press me to give my views on such a new, but important subject. It is only a few days since I came in your midst. It will not do that I should so soon become your judge. The responsibility of a judgment in such a momentous matter is too great. I cannot accept it."

But when the same pressing request was repeated by nine-tenths of that vast assembly of priests, and that the archbishop pressed him more and more to pronounce his sentence, he raised his eyes and hands to heaven, and made a silent but ardent prayer to God. His countenance took an air of dignity, which I might call majesty, which gave him more the appearance of an old prophet than of a man of our day. Then casting his eyes upon his audience, he remained a considerable time meditating. All eyes were upon him, anxiously waiting for the sentence. There was an air of grandeur in him at that moment, which seemed to tell us that the priest blood of the great kings of France was flowing in his veins. At last, he opened his lips, but it was again pressingly to request me to settle the difficulty with the archbishop among ourselves, and to discharge him of that responsibility. But we both refused again to grant him his request, and pressed him to give his judgment. All this time I was standing, having publicly said that I would never sit again at that table unless that insult was wiped away.

Then he said with unspeakable dignity: "My Lord of Quebec! Here, before us, is our young priest, Mr. Chiniquy, who, once on his knees, in the presence of God and his angels, for the love of Jesus Christ, the good of his own soul and the good of his country, has promised never to drink! We are the witnesses that he is faithful to his promise, though he has been pressed to break it by your lordship. And because he keeps his pledge with such heroism, your lordship has called him a fanatic! Now, I am requested by everyone here to pronounce my verdict on that painful occurrence. Here it is. Mr. Chiniquy drinks no wine! But, if I look through the past ages, when God Himself was ruling His own people, through His prophets, I see Samson, who, by the special order of God, never drank wine or any other intoxicating drink. If from the Old Testament I pass to the New, I see John the Baptist, the precursor of our Saviour, Jesus Christ, who, to obey the command of God, never drank any wine! When I look at Mr. Chiniquy, and see Samson at his right hand to protect him, and John the Baptist at his left to bless him, I find his position so strong and impregnable, that I would not dare attack or condemn him!" These words were pronounced in the most eloquent and dignified manner, and were listened to with a most respectful and breathless attention.

Bishop de Nancy, keeping his gravity, sat down, emptied his wine glass into a tumbler, filled it with water and drank to my health.

The poor archbishop was so completely confounded and humiliated that everyone felt for him. The few minutes spent at the table, after this extraordinary act of justice, seemed oppressive to everyone. Scarcely anyone dared look at his neighbour, or speak, except in a low and subdued tone, as when a great calamity has just occurred. Nobody thought of drinking his wine; and the health of the Bishop de Nancy was left undrunk. But a good number of priests filled their glasses with water, and giving me a silent sign of approbation, drank to my health. The society of temperance had been dragged by her enemies to the battlefield, to be destroyed; but she bravely fought, and gained the victory. Now, she was called to begin her triumphant march through Canada.

Continue to Chapter Thirty-Six