Fifty Years

in the Church

of Rome

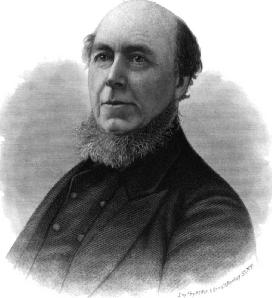

by Charles Chiniquy

Charles Chiniquy

1809-1899

CHAPTER 24

In the beginning of September, 1834, the Bishop Synaie gave me the enviable position of one of the vicars of St. Roch, Quebec, where the Rev. Mr. Tetu had been curate for about a year. He was one of the seventeen children of Mr. Francis Tetu, one of the most respectable and wealthy farmers of St. Thomas. Such was the amiability of character of my new curate, that I never saw him in bad humour a single time during the four years that it was my fortune to work under him in that parish. And although in my daily intercourse with him I sometimes unintentionally sorely tried his patience, I never heard an unkind word proceed from his lips.

He was a fine looking man, tall and well built, large forehead, blue eyes, a remarkably fine nose and rosy lips, only a little to feminine. His skin was very white for a man, but his fine short whiskers, which he knew so well how to trim, gave his whole mien a manly and pleasant appearance.

He was the finest penman I ever saw; and by far the most skilful skater of the country. Nothing could surpass the agility and perfection with which he used to write his name on the ice with his skates. He was also fond of fast horses, and knew, to perfection, how to handle the most unmanageable steeds of Quebec. He really looked like Phaeton when, in a light and beautiful buggy, he held the reins of the fiery coursers which the rich bourgeois of the city like to trust to him once or twice a week, that he might take a ride with one of his vicars to the surrounding country. Mr. Tetu was also fond of fine cigars and choice chewing tobacco. Like the late Pope Pius IX., he also constantly used the snuff box. He would have been a pretty good preacher, had he not been born with a natural horror of books. I very seldom saw in his hands any other books than his breviary, and some treatises on the catechism: a book in his hands had almost the effect of opium on one's brains, it put him to sleep. One day, when I had finished reading a volume of Tertullian, he felt much interested in what I said of the eloquence and learning of that celebrated Father of the Church, and expressed a desire to read it. I smilingly asked him if he were more than usual in need of sleep. He seriously answered me that he really wanted to read that work, and that he wished to begin its study just then. I lent him the volume, and he went immediately to his room in order to enrich his mind with the treasures of eloquence and wisdom of that celebrated writer of the primitive church. Half an hour after, suspecting what would occur, I went down to his room, and noiselessly opening the door, I found my dear Mr. Tetu sleeping on his soft sofa, and snoring to his heart's content, while Tertullian was lying on the floor! I ran to the rooms of the other vicars, and told them: "Come and see how our good curate is studying Tertullian!"

There is no need to say that we had a hearty laugh at his expense. Unfortunately, the noise we made awoke him, and we then asked him: "What do you think of Tertullian?"

He rubbed his eyes, and answered, "Well, well! what is the matter? Are you not four very wicked men to laugh at the human frailties of your curate?" We for a while called him Father Tertullian.

Another day he requested me to give him some English lessons. For, though my knowledge of English was then very limited, I was the only one of five priests who understood and could speak a few words in that language. I answered him that it would be as pleasant as it was easy for me to teach the little I knew of it, and I advised him to subscribe for the "Quebec Gazette," that I might profit by the interesting matter which that paper used to give to its readers; and at the same time I should teach him to read and understand its contents.

The third time that I went to his room to give him his lesson, he gravely asked me: "Have you ever seen `General Cargo?'"

I was at first puzzled by that question, and answered him: "I never heard that there was any military officer by the name of `General Cargo.' How do you know that there is such a general in the world?"

He quickly answered: "There is surely a `General Cargo' somewhere in England or America, and he must be very rich; for see the large number of ships which bear his name, and have entered the port of Quebec, these last few days!"

Seeing the strange mistake, and finding his ignorance so wonderful, I burst into a fit of uncontrollable laughter. I could not answer a word, but cried at the top of my voice: "General Cargo! General Cargo!"

The poor curate, stunned by my laughing, looked at me in amazement. But, unable to understand its cause, he asked me: "Why do you laugh?" But the more stupefied he was, the more I laughed, unable to say anything but "General Cargo! General Cargo!"

The three other vicars, hearing the noise, hastily came from their rooms to learn its cause, and get a good laugh also. But I was so completely beside myself with laughing, that I could not answer their questions in any other way than by crying, "General Cargo! General Cargo!"

The puzzled curate tried then to give them some explanation of that mystery, saying with the greatest naivete: "I cannot see why our little Father Chiniquy is laughing so convulsively. I put to him a very simple question, when he entered my room to give me my English lesson. I simply asked him if he had ever seen `General Cargo,' who has sent so many ships to our port these last few days, and added that that general must be very rich, since he has so many ships on he sea!" The three vicars saw the point, and without being able to answer him a word, they burst into such fits of laughter, that the poor curate felt more than ever puzzled.

"Are you crazy?" he said. "What makes you laugh so when I put to you such a simple question? Do you not know anything about that `General Cargo,' who surely must live somewhere, and be very rich, since he sends so many vessels to our port that they fill nearly two columns of the `Quebec Gazette'?"

These remarks of the poor curate brought such a new storm of irrepressible laughter from us all as we never experienced in our whole lives. It took us some time to sufficiently master our feelings to tell him that "General Cargo" was not the name of any individual, but only the technical words to say that the ships were laden with general goods.

The next morning, the young and jovial vicars gave the story to their friends, and the people of Quebec had a hearty laugh at the expense of our friend. From that time we called our good curate by the name of "General Cargo,' and he was so good-natured that he joined with us in joking at his own expense. It would require too much space were I to publish all the comic blunders of that good man, and so I shall give only one more.

On one of the coldest days of January, 1835, a merchant of seal skins came to the parsonage with some of the best specimens of his merchandise, that we might buy them to make overcoats, for in those days the overcoats of buffalo or raccoon skins were not yet thought of. Our richest men used to have beaver overcoats, but the rest of the people had to be contented with Canada seal skins; a beaver overcoat could not be had for less than 200 dollars.

Mr. Tetu was anxious to buy the skins; his only difficulty was the high price asked by the merchant. For nearly an hour he had turned over and over again the beautiful skins, and has spent all his eloquence on trying to bring down their price, when the sexton arrived, and told him, respectfully, "Mr. le Cure, there are a couple of people waiting for you with a child to be baptized."

"Very well," said the curate, "I will go immediately;" and addressed the merchant, he said,"Please wait a moment; I will not be long absent."

In two minutes after the curate had donned the surplice, and was going at full speed through the prayers and ceremonies of baptism. For, to be fair and true towards Mr. Tetu (and I might say the same thing of the greatest part of the priests I have known), it must be acknowledged that he was very exact in all his ministerial duties; yet he was, in this case, going through them by steam, if not by electricity. He was soon at the end. But, after the sacrament was administered, we were enjoined, then, to repeat an exhortation to the godfathers and godmothers, from the ritual which we all knew by heart, and which began with these words: "Godfathers and Godmothers: You have brought a sinner to the church, but you will take back a saint!"

As the vestry was full of people who had come to confess, Mr. Tetu thought that it was his duty to speak with more emphasis than usual, in order to have his instructions heard and felt by everyone, but instead of saying, "Godfather and Godmother, You have brought a sinner to the church, you will take back a saint!" he, with great force and unction said: "Godfather and Godmother, You have brought a sinner to the church, you will take back a seal skin!"

No words can describe the uncontrollable burst and roar of laughter among the crowd, when they heard that the baptized child was just changed into a "seal skin." Unable to contain themselves, or do any serious thing, they left the vestry to go home and laugh to their heart's content.

But the most comic part of this blunder was the sang froid and the calmness with which Mr. Tetu, turning towards me, asked: "Will you be kind enough to tell me the cause of that indecent and universal laughing in the midst of such a solemn action as the baptism of this child?"

I tried to tell him his blunder, but for some time it was impossible to express myself. My laughing propensities were so much excited, and the convulsive laughter of the whole multitude made such a noise, that he would not have heard me had I been able to answer him. It was only when the greatest part of the crowd had left that I could reveal to Mr. Tetu that he had changed the baptized baby into a "seal skin!" He heartily laughed at his own blunder, and calmly went back to buy his seal skins. The next day the story went from house to house in Quebec, and caused everywhere such a laugh as they had not had since the birth of "General Cargo."

That priest was a good type of the greatest part of the priests of Canada. Fine fellows social and jovial gentlemen as fond of smoking their cigars as of chewing their tobacco and using their snuff; fond of fast horses; repeating the prayers of their breviary and going through the performance of their ministerial duties with as much speed as possible. With a good number of books in their libraries, but knowing nothing of them but the titles. Possessing the Bible, but ignorant of its contents, believing that they had the light, when they were in awful darkness; preaching the most monstrous doctrines as the gospel of truth; considering themselves the only true Christians in the world, when they worshipped the most contemptible idols made with hands. Absolutely ignorant of the Word of God, while they proclaimed and believed themselves to be the lights of the world. Unfortunate, blind men, leading the blind into the ditch!

Continue to Chapter Twenty-Five